Can we trust anything we see? Or hear? Last week saw the news that James Earl Jones was retiring from his role voicing Darth Vader in the Star Wars franchise, and farming it out to AI. Brief musings follow.

Specifically, Jones was licensing the rights to his voice to Lucasfilm so they could recreate the voice via AI. Synthesizing voices and images is now something even the public (or at least the data-savvy public) can do. In related news from last week, the research lab OpenAI removed the waitlist for its DALL-E platform, which can create startlingly real images from a simple text phrase (see https://openai.com/blog/dall-e-now-available-in-beta/). Similar tools exist to mimic a person’s voice (see https://beebom.com/deepfake-ai-voice-generator-mimic-celebrity-voices/).

AI’s ability to mimic humans to the point where synthetic images and voices are virtually indistinguishable from the real thing creates possibilities for all sorts of mischief. This new frontier for AI is a source of great concern to the community that worries about ethical issues in AI.

But did James Earl Jones’ rights to his own voice come naturally? Or did he secure those rights in an earlier Star Wars contract?

The Cowardly Lion versus Lestoil

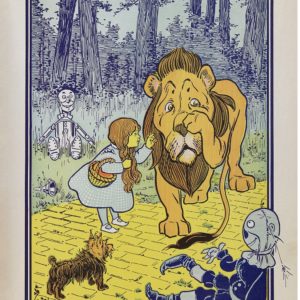

It turns out that rights to our own image and voice are secured to us by a “right of publicity.” This was tested somewhat comically in a legal contest between Bert Lahr, best known as the Cowardly Lion in the Wizard of Oz, and Adell Chemical Company, best known as the maker of Lestoil cleaner.

Enter the Duck

Lahr claimed that his distinctive voice was unlawfully appropriated by Lestoil in a cartoon commercial featuring a duck. Specifically, Adell hired “as the voice of the aforesaid duck, an actor who specialized in imitating the vocal sounds of the plaintiff.” He further claimed that the “vast public television audience and the entertainment industry” believed that the words spoken and the comic sounds made by the cartoon duck were supplied and made by Lahr, “trading upon his fame and renown.”

Furthermore, Lahr alleged damages because people might now believe he had been reduced to making anonymous duck commercials. And, to add insult to injury, not making them well. Lahr stated that the quality of the duck’s voice in the commercial was inferior to what he could have produced and led people to think that his abilities had deteriorated. Lahr’s 1961 case is often cited in studies of the “right of publicity.” He did not prevail, but the ruling did not undercut the basic right of publicity. The court simply felt that his damage claim,

“Your (anonymous) commercial sounded like me, but not so good,” was too broad, and would lead to excessive litigation. The right of publicity is now deeply embedded in common and statutory law at the state level, sometimes as part of a “right to privacy.”

Moral #1

If it looks like a duck and walks like a duck, it might be AI.

Moral #2

More seriously, there are a couple of lessons for those practicing cutting edge AI. Some new technologies and tools are so alluring that they just call out to be pursued and perfected as objects of technical wonder in and of themselves, without regard to context, purpose or consequences, including legal consequences. Ultimately, responsible data scientists need to consider how a cool new technology will ultimately serve larger legitimate business or organizational objectives (and be aware of the harm that might be caused along the way). Practitioners of emerging technologies are understandably resistant to regulations and laws aimed at restricting what they can do, and, indeed, targeted laws like that are often counter-productive in the long run. The story of the “right of publicity” reminds us that, in the absence of AI-centric laws, it is still not the Wild West. There are time-honored legal constraints long predating the advent of AI that still must be obeyed by those developing AI applications.