Dr. Carlos Carcach is Professor & Director of the Center for Public Policy at the Escuela Superior de Economía y Negocios (ESEN) in Santa Tecla, El Salvador, and coordinator of ESEN’s post-graduate program in predictive analytics, which offers online instruction in partnership with Statistics.com, using courses from our online certificate program.

I suggested to Carcach that perhaps an epidemiological model might fit the situation – the spread of an infectious disease. The term “epidemiological criminology” was first proposed for this phenomenon in 2009 (see Akers and Lanier, in the American Journal of Public Health). Carcach allowed that there might be merit in this but thought a cancer model was more appropriate. For one thing, cancer tends to mutate as it spreads, changing in form, and the criminal activity he was tracking did likewise. For another, infection tends to produce a defensive response in the body it infects, usually overcoming the infection, while cancer does not excite an immediate counterattack from its host.

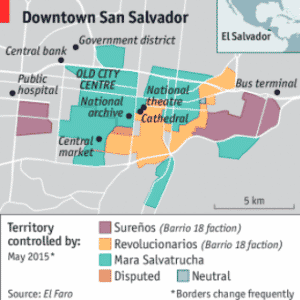

Carcach was pessimistic about the potential for an organic evolution of society in which the role of the gangs would wither. He said that their activities at the local level were not new – they had been preceded by local actors whose protection and extortion rackets were similar in character, but not in intensity. The gangs, informed and strengthened by their US experiences and connections, simply took control of these activities, and gave them greater intensity. They built the local units up into a hierarchical organization resembling a franchise operation, with an average size of 15 members in the bottom-most units. When they got bigger than that, they tended to split up.

Carcach believes that only the extension and strengthening of basic government services (water, sewage, education) into rural areas would provide the external reinforcement of society against gang growth.

Covid

I checked back with Carcach recently, curious about the effect that Covid has had on gang activity. As with so much social science research, it is hard to separate one thing from another. Here’s what he said:

It is not clear whether gang activity has been affected by the Covid emergency or not. At the beginning of the lockdown, there were some news reports of gangs enforcing it in their territories, and that they declared a sort of temporary suspension of extortion payments. But none of these claims can be verified. Official data indicate a decline in extortions and homicides but it is not possible to separate the Covid impact from the apparent effectiveness of the Plan de Control Territorial. In addition, the El Faro newspaper published a report uncovering an agreement between gangs and the Bukele government, allegedly to reduce homicides and extortions.